Decoding Pilates: Essential Terms Every Student Should Know

- Sheela Cheong

- Feb 23, 2024

- 6 min read

Embarking on a journey into the world of Pilates can feel like stepping into a new language. From "core" to "neutral spine," the vocabulary of Pilates is rich with terms that hold the keys to unlocking the practice's transformative power.

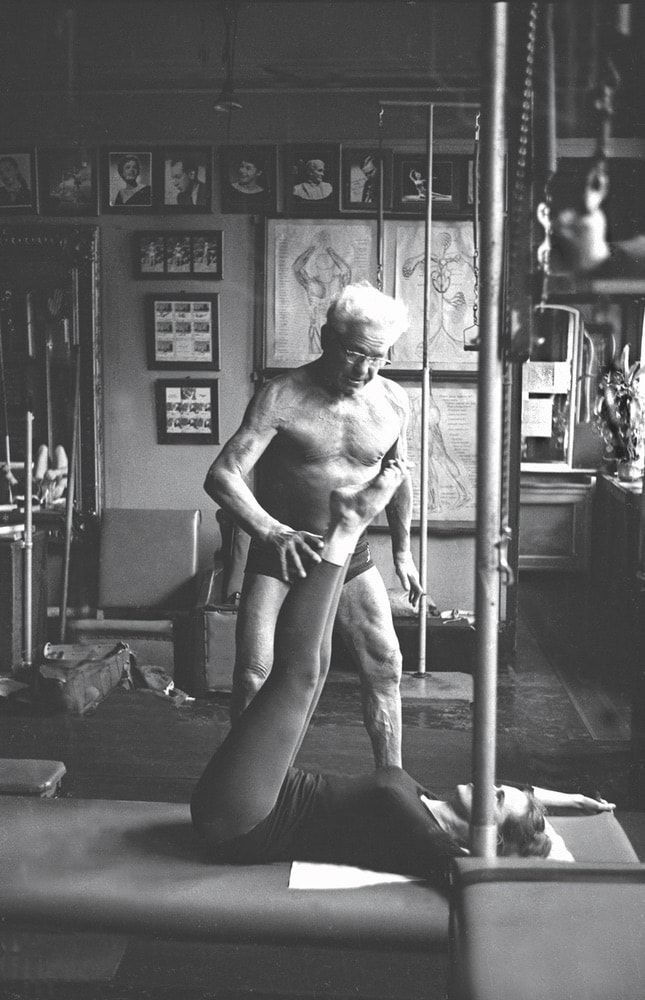

Pilates founder Joseph Pilates (standing) works with a client at his gym in New York City, 4 Oct, 1961.

Whether you're a seasoned practitioner or a newcomer to the mat, understanding these key terms is essential for:

mastering Pilates technique,

refining body awareness, and

achieving optimal results.

In this comprehensive guide, we'll delve into the essential vocabulary of Pilates, breaking down each term to demystify its meaning and significance within the practice. So, grab your mat, take a deep breath, and let's dive into the world of Pilates terminology together.

Three main sections of the spine

1) NEUTRAL SPINE

In Pilates, neutral spine refers to the optimal alignment of the spine where the natural curves of the spine are maintained. It's neither excessively arched nor overly rounded, but rather in a balanced position that promotes stability, proper muscle engagement, and efficient movement mechanics.

The three primary curves of the spine—cervical (neck), thoracic (mid-back), and lumbar (lower back)—are aligned in a way that minimises stress and strain on the spine and surrounding muscles.

Neutral spine is emphasised in Pilates because it allows for optimal engagement of the core muscles, particularly the deep stabilising muscles such as the transverse abdominis and pelvic floor muscles. When the spine is in neutral alignment, these core muscles can effectively support the spine, pelvis, and surrounding structures, providing stability and control during movement.

However, it's important to understand that neutral spine is not always the "best" or most appropriate alignment for every situation or individual. Here's why:

Neutral Spine is Not Always Ideal: Depending on the exercise, modifying the spine position may be necessary to accommodate varying body types, injuries, or specific goals. For example, in exercises like the pelvic curl or bridging, intentionally articulating the spine through flexion and extension can help improve spinal mobility and strengthen different muscle groups.

Individual Variation: Each person's body is unique, and what constitutes neutral spine for one individual may differ from another. Factors such as bone structure, muscle imbalances, and previous injuries can influence spinal alignment and movement patterns. For some individuals, maintaining a strict neutral spine alignment may not be feasible or comfortable.

Functional Movement: In real-life activities and sports, the spine often moves through a range of positions beyond neutral. Learning to control and stabilise the spine in various positions, including flexion, extension, rotation, and lateral flexion, is essential for functional movement and injury prevention. While neutral spine provides a stable base, the ability to move the spine dynamically and adapt to different situations is equally important.

Contextual Considerations: The appropriateness of neutral spine depends on the context of the exercise, the individual's biomechanics, and any specific considerations such as injuries or limitations. In some cases, intentionally moving away from neutral spine can be beneficial for targeting specific muscle groups, improving mobility, or rehabilitating injuries under the guidance of a qualified instructor.

In essence, while neutral spine serves as a foundational concept in Pilates, it's essential to recognize the value of movement variability and individualised modifications. Pilates encourages mindful movement, body awareness, and adaptability to support overall health and function.

Rather than rigidly adhering to a single ideal posture, practitioners should focus on finding balance, stability, and ease of movement within their own bodies.

What does "neutral spine" look like?

Everyone's "neutral spine" alignment does not look the same. The exact positioning of neutral spine can vary significantly from person to person due to factors such as:

Bone Structure: The shape and size of the vertebrae, as well as the curvature of the spine, can vary among individuals. Some people naturally have more pronounced curves in certain areas of the spine, which can affect their neutral spine alignment.

Muscle Imbalances: Differences in muscle strength, flexibility, and activation patterns can influence how the spine aligns in a neutral position. Imbalances in the muscles surrounding the spine, pelvis, and core can result in deviations from the "typical" neutral spine alignment.

Postural Habits: Daily habits, occupational activities, and lifestyle factors can impact spinal alignment over time. For example, prolonged sitting, standing, or repetitive movements may contribute to postural deviations that affect neutral spine alignment.

Injuries and Conditions: Previous injuries, spinal conditions, and musculoskeletal disorders can alter the natural alignment of the spine and affect an individual's ability to achieve neutral spine alignment. In some cases, modifications may be necessary to accommodate these factors while maintaining safety and stability.

Individual Preferences: Some individuals may have personal preferences or comfort levels that influence how they position their spine in neutral alignment. While certain guidelines apply to neutral spine alignment, there is also room for individual variation based on what feels most natural and comfortable for each person.

Overall, neutral spine alignment is a dynamic concept that takes into account individual differences in anatomy, movement patterns, and biomechanics.

While there are general principles to guide alignment and movement in Pilates and other forms of exercise, it's important to recognize and respect the uniqueness of each person's body and alignment preferences.

Working with a qualified instructor can help individuals understand their own neutral spine alignment and make appropriate adjustments to support optimal movement and function.

Neutral Spine & Imprinted Spine

2) IMPRINT

Imprint is a position where you gently press your lower back into the mat, engaging your core muscles and creating a slight posterior (backward) pelvic tilt. In Pilates, imprinting is often used to establish a stable and supported position for the spine during exercises where the legs are lifted or moved away from the body.

By imprinting, you help maintain the natural curves of your spine while providing support to the lower back and pelvis. It's important to maintain a sense of connection with your core muscles and avoid excessive flattening of the lower back to prevent strain or discomfort.

3) C-CURVE SPINE

The C-curve spine is a position where the spine forms a gentle "C" shape, often used in Pilates exercises to engage the core muscles and promote spinal flexibility.

In this position, the pelvis tilts slightly backward, and the abdominals draw inward, rounding the lower back and lengthening the spine forward. The C-curve position helps activate the deep abdominal muscles, support spinal flexion, and improve body awareness. It's commonly used in exercises like the Pilates roll-up to strengthen the core and enhance spinal mobility.

4) CORE

Your core refers to the group of muscles in your abdomen, lower back, pelvis, and hips that work together to provide stability, support, and control for your spine and pelvis during movement.

In Pilates, core strength and stability are emphasised as the foundation for all exercises. Strengthening your core helps improve posture, balance, and overall functional movement. Pilates exercises target deep core muscles such as the transverse abdominis and pelvic floor muscles, as well as the more superficial abdominal muscles like the rectus abdominis (your "six-pack") and obliques.

5) TRANSVERSE ABDOMINIS

The transverse abdominis is the deepest layer of abdominal muscles that wraps around the abdomen like a corset, providing stability and support for the spine and pelvis. In Pilates, the transverse abdominis is often referred to as the "corset muscle" because of its role in stabilising the core and maintaining proper alignment.

Activating the transverse abdominis helps create a strong and stable foundation for movement, enhances postural alignment, and protects the spine from injury. It's a key muscle targeted in Pilates exercises to develop core strength and improve overall body control.

Pelvic floor muscles

6) PELVIC FLOOR

The pelvic floor refers to a group of muscles and connective tissues that form a hammock-like structure at the bottom of the pelvis, supporting the bladder, uterus, and rectum. The pelvic floor plays a crucial role in maintaining continence, supporting pelvic organs, and stabilising the pelvis and spine.

In Pilates, awareness and engagement of the pelvic floor muscles are emphasised to enhance core stability, improve posture, and prevent pelvic floor dysfunction. Strengthening the pelvic floor muscles through specific exercises can help improve bladder control, alleviate lower back pain, and enhance overall pelvic health.

Is the pelvic floor part of the core?

The pelvic floor is considered part of the core musculature due to its vital role in providing stability, support, and functional control to the trunk, pelvis, and spine.

Structural Support: The pelvic floor consists of a group of muscles, ligaments, and connective tissues located at the base of the pelvis. These structures form a supportive hammock-like network that helps hold the pelvic organs in place and maintain optimal pelvic alignment.

Stability and Control: Like other core muscles, the pelvic floor muscles contribute to the stability and control of the trunk and pelvis during movement and weight-bearing activities. When engaged, the pelvic floor helps maintain proper alignment of the pelvis and spine, providing a stable foundation for movement.

Function in Intra-Abdominal Pressure Regulation: The pelvic floor plays a crucial role in regulating intra-abdominal pressure, which is the pressure within the abdominal cavity. By contracting and relaxing in coordination with other core muscles, the pelvic floor helps manage intra-abdominal pressure during activities such as lifting, coughing, sneezing, and breathing.

Integration with Core Function: The pelvic floor works synergistically with other core muscles, including the transverse abdominis, internal and external obliques, and multifidus muscles, to provide comprehensive core stability and support. Optimal coordination and activation of these muscles contribute to efficient movement patterns and reduce the risk of injury.

Impact on Functional Activities: Dysfunction or weakness in the pelvic floor muscles can lead to various issues, including urinary incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse, and lower back pain. Strengthening and maintaining optimal function of the pelvic floor are essential for promoting urinary and bowel continence, supporting pelvic health, and enhancing overall quality of life.

In summary, the pelvic floor is considered an integral part of the core due to its role in providing stability, support, and functional control to the trunk, pelvis, and spine. By incorporating pelvic floor exercises and awareness into core-focused training programs, you can improve your overall core strength, stability, and functional movement patterns.

Neutral spine, backward pelvic tilt, forward pelvic tilt

7) PELVIC ALIGNMENT

In Pilates, pelvic alignment refers to the optimal positioning of the pelvis to support proper spinal alignment and facilitate efficient movement patterns. The pelvis serves as the foundation of the spine and plays a crucial role in maintaining stability, balance, and mobility during Pilates exercises.

Posterior Pelvic Tilt:

Imagine your pelvis like a bowl. When you do a posterior pelvic tilt, you're tipping the top of the bowl backward, and your tailbone moves closer to your heels.

It's like tucking your tailbone under.

This movement often happens when you engage your abs and squeeze your buttocks.

It helps stabilise your lower back and pelvis, especially during exercises where you need a strong core and good posture.

Anterior Pelvic Tilt:

Now, picture your pelvis tilting forward, like the front of the bowl is spilling forward.

With anterior pelvic tilt, your lower back arches more, and your belly might stick out a bit.

This often happens when your hip flexor muscles are tight and pull your pelvis forward.

While a little anterior tilt is normal, too much can strain your lower back and affect your posture negatively.

Both movements are natural parts of how your body moves, but it's important to keep them balanced. In exercises and daily activities, being aware of your pelvic tilt can help you maintain good posture and prevent discomfort or injury in your lower back and hips.

Are Backward / Forward Pelvic Tilts "Bad" Posture?

It is inaccurate and misguided to categorise anterior and posterior pelvic tilts as examples of or causes of bad posture because these movements are natural and essential components of healthy spinal alignment and movement. Here's why:

Natural Range of Motion: The pelvis is designed to move through a range of positions, including anterior / posterior pelvic tilt. These movements are inherent to the body's biomechanics and play crucial roles in supporting various activities and maintaining dynamic stability.

Functional Movement: Anterior / posterior pelvic tilts are integral to functional movement patterns such as walking, running, bending, and lifting. These movements facilitate efficient transfer of force between the upper and lower body, promote optimal muscle activation, and contribute to overall movement efficiency.

Adaptation to Environment: Postural alignment is influenced by a multitude of factors including genetics, lifestyle, and habitual movement patterns. While excessive or prolonged anterior or posterior pelvic tilting may contribute to discomfort or postural issues in some individuals, it is often a symptom rather than the cause of underlying biomechanical imbalances or movement dysfunctions.

Individual Variability: Postural alignment is highly individualised and can vary widely among individuals based on their bone structure, muscle imbalances, and movement habits. What may appear as "bad posture" in one person may be perfectly functional and comfortable for another.

Instead of focusing solely on pelvic tilt as a marker of good or bad posture, the emphasis should be on improving overall mobility, stability, and control of the body and its joints. This involves cultivating body awareness, addressing muscular imbalances, and developing movement strategies that promote optimal alignment and function in various activities.

THERE IS NO SUCH THING AS "BAD POSTURE"

There is no such thing as an inherently bad posture or position.

The specific posture itself is not the most critical factor to contemplate. Instead, these are the things to consider:

How many times/day is that posture used?

How long are you in that posture when you use it? How much time in total each day?

Can you get out of that posture easily?

Do you have many different postures to choose from?

Do you have the body control to modify the position effectively to diversify your “posture menu”?

Do you have the muscular control and endurance to sustain the postures you need for the demands of your life?

If you are “stuck” in a slouched posture all the time, THAT is when it can become a problem.

Prolonged sitting, standing, or maintaining any posture without movement can lead to muscle stiffness, joint compression, and discomfort.

In summary, Pilates terminology, including terms like "neutral spine," isn't about rigidly adhering to a fixed idea of "good posture."

Instead, it serves as a practical guide to support ease of movement and address imbalances or weaknesses in the body. These terms provide a roadmap for cultivating a balanced and functional body, encouraging individuals to move freely and strengthen areas that may need attention.

The essence lies in fostering a body that moves with efficiency and resilience, promoting overall well-being through the principles embedded in Pilates terminology: Breath, concentration, control, precision, centre and flow.

References:

'Is There Really Such Thing As "Bad Posture"?', (1 August 2020).

'Is It Really Your Bad Posture Causing You Pain?' (9 March, 2023). https://www.hickshealth.com/is-it-really-your-bad-posture-causing-your-pain/

Comments