Architectural Alignment: How Ballet & Iyengar Yoga Build Powerful Posture

- Sheela Cheong

- 17 hours ago

- 9 min read

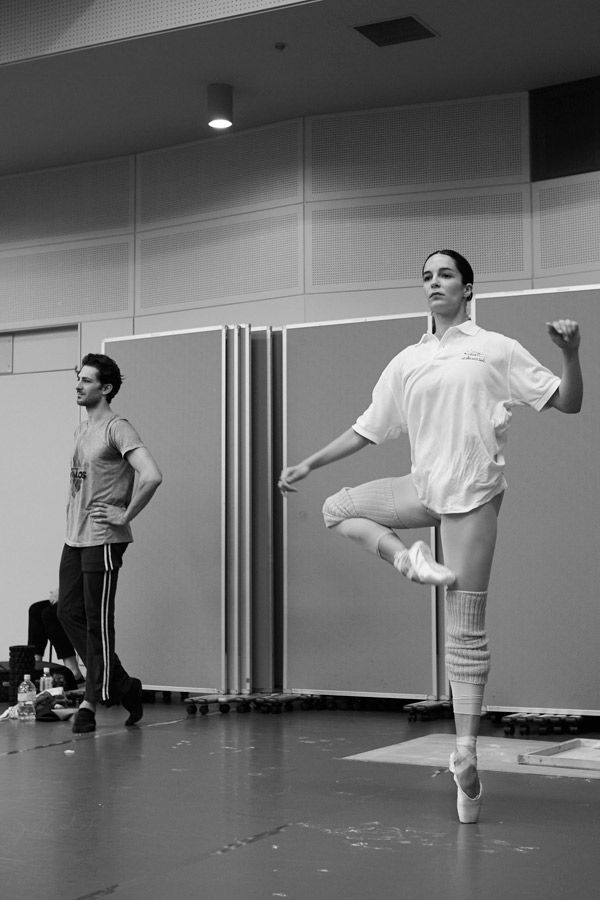

Have you ever wondered why dancers seem to stand effortlessly tall — not rigid or forced, but naturally lifted and balanced?

Before I took my first ballet class, the first yoga system I practised — almost 20 years ago — was Iyengar yoga.

Fast forward to me in a ballet studio -- what struck me immediately was how familiar the cues sounded. They were almost identical to what I used to hear from my Iyengar teacher:

“Imagine your body between two panes of glass.”

“Move as if you’re a slice of toast in a toaster*."

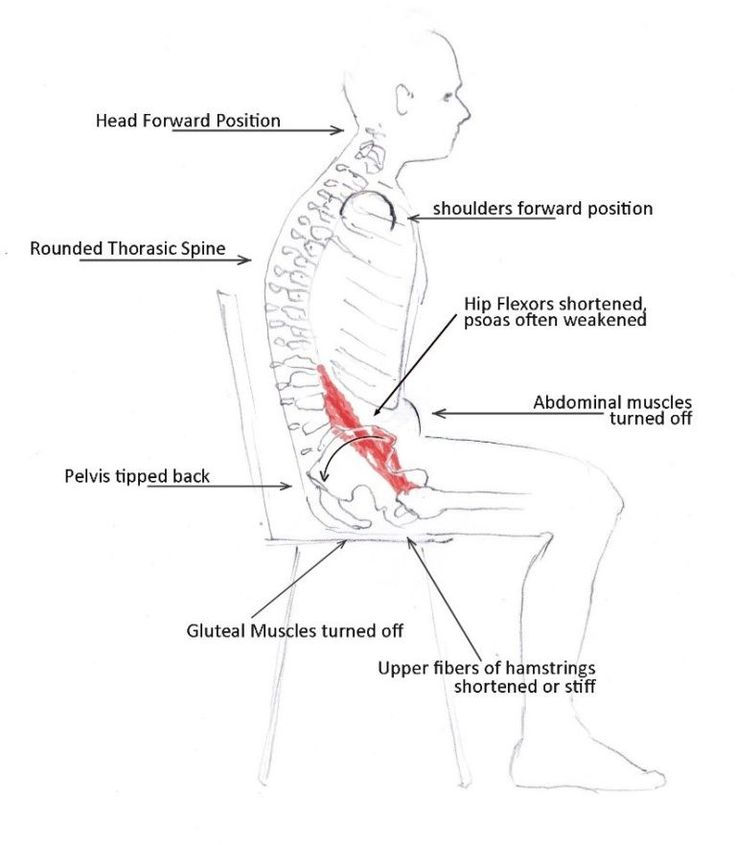

In an era where many of us spend hours hunched over devices, posture is often reduced to a simple command: “sit up straight.” But both ballet technique and Iyengar yoga offer something far more sophisticated — a structural template for alignment built on geometry, directional energy, and intelligent muscular activation.

Before exploring the shared alignment principles between these two disciplines, it helps to understand where each method came from — and why both developed such a deep respect for anatomical precision and structural balance. (*While modern yoga teaching has evolved away from overly literal alignment rules, I still believe these visualisations have an important place. They create a powerful visual language for understanding vertical stacking, centre of gravity, and balanced muscular activation.)

This article is organised into two complementary parts.

Part 1 is for movement educators — ballet, Pilates, and yoga teachers. It dives into the history, anatomy, and alignment frameworks behind these practices, helping you understand why they work and how to integrate them into teaching or movement coaching.

Part 2 is for students, practitioners, or anyone interested in improving their own posture. It translates the same principles into common postural challenges — like rounded shoulders, neck tension, and slouched upper backs — showing how a practice inspired by ballet and Iyengar yoga can support a stronger, more balanced body.

You can read the article in full, or focus on the section that best fits your needs.

PART ONE

🩰 Classical Ballet Technique — Origins & Evolution

Originated in Italian Renaissance courts (15th–16th century) before developing strongly in French royal academies.

Formalised under King Louis XIV, who founded the Académie Royale de Danse in 1661.

Early ballet training emphasised posture, turnout, and geometric lines for aesthetic clarity and technical consistency.

Over centuries, codified methods (e.g., Vaganova, Cecchetti, RAD) refined alignment principles to improve efficiency and reduce injury.

Modern ballet pedagogy blends artistry with increasing understanding of anatomy and biomechanics.

Key Idea: Precision of line and posture wasn’t only aesthetic — it was also structural and functional.

🧘 Iyengar Yoga — Origins & Development

Developed by B.K.S. Iyengar (1918–2014), a student of T. Krishnamacharya.

Emerged in the mid-20th century with a strong focus on alignment, therapeutic application, and accessibility.

Introduced the innovative use of props to help practitioners experience accurate anatomical positioning.

Emphasised holding poses with awareness to build proprioception and muscular intelligence.

Became globally recognised for its systematic approach to posture, structural balance, and injury-sensitive practice.

Key Idea: Iyengar yoga reframed yoga practice through the lens of anatomical precision and functional alignment.

🔧 A Parallel Evolution: Pilates and the Dance World

Around the same period that structured movement systems were evolving, Joseph Pilates began developing what he called Contrology — a method built around precision, core stability, and efficient movement mechanics. Some of his earliest dedicated students were dancers in New York, many of whom sought out his work to recover from injury and improve technical control.

Because of this close relationship with the dance community, Pilates training — particularly on the reformer — naturally adopted many of the same alignment priorities seen in ballet: spinal organisation, balanced muscular activation, and strength that supports range rather than forcing it. Today, it remains one of the most widely used conditioning methods among dancers for exactly these reasons.

Ballet Technique vs Iyengar Yoga: Alignment, Posture & Directional Energy

1. Axial Elongation (Length Through the Spine)

Common Principle: Both systems prioritise decompression and vertical lift.

Ballet

“Pull up” through the crown of the head while grounding through the legs.

Neutral pelvis with lumbar length — avoid excessive anterior tilt (“duck bum”).

Ribcage stacked over pelvis to maintain vertical integrity during movement.

Iyengar Yoga

Strong emphasis on axial extension in virtually every pose (Tadasana is the reference).

Instructional cues: lift sternum without flaring ribs; lengthen tailbone downward.

Uses props (blocks, wall ropes) to help students experience true spinal elongation.

Shared Mechanism

Eccentric activation of deep spinal stabilisers.

Reduction of compressive loading on vertebrae.

Length + stability rather than rigidity.

2. Directional Energy & Oppositional Forces

Common Principle: Movement is created through opposing vectors rather than brute force.

Ballet

“Energy up and down simultaneously”: legs press into floor while torso lifts upward.

In extensions: working leg lengthens outward while standing leg roots downward.

Port de bras uses expansion through fingertips while scapula stabilises.

Iyengar Yoga

Clear vector-based cues: press thighs back while lifting kneecaps; reach arms up while grounding feet.

Oppositional actions used to stabilise joints and prevent collapse.

Teachers often describe energy radiating from centre to periphery.

Shared Outcome

Efficient force transfer.

Joint centration.

Stability without muscular gripping.

3. Geometric Precision & Symmetry

Common Principle: Alignment is treated almost mathematically.

Ballet

Lines and angles: turnout from hips, knee tracking over toes, square hips in arabesque.

Spatial geometry in positions (first position symmetry, fifth position stacking).

Clean planes and rotational control define aesthetic and safety.

Iyengar Yoga

Precise placement of limbs (e.g., triangle pose: arms in one line, torso in defined plane).

Teachers may physically adjust millimetre-level differences.

Props used to reveal asymmetries and deviations.

Shared Objective

Proprioceptive awareness.

Balanced load distribution.

Reproducible alignment patterns.

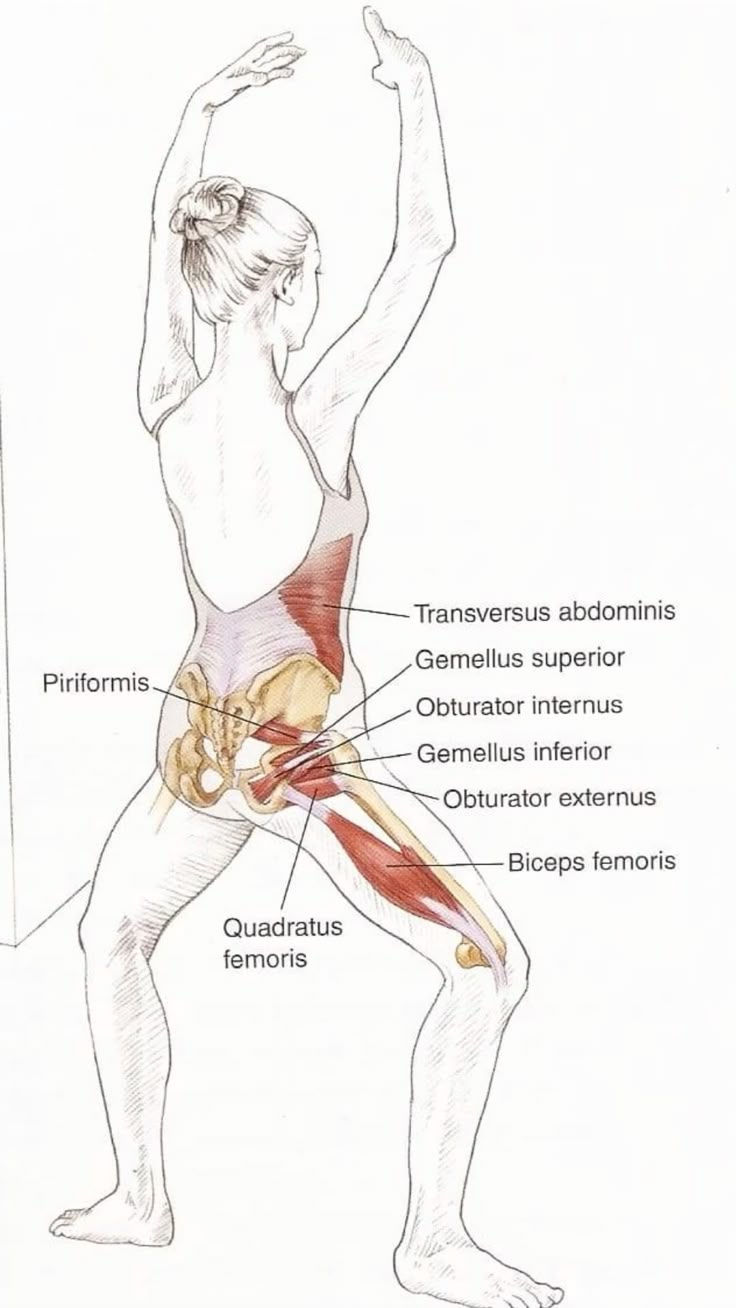

4. Active Stability vs Passive Flexibility

Common Principle: Strength supports range of motion.

Ballet

Turnout maintained by deep hip external rotators — not passive foot positioning.

Extensions require active hamstring and core engagement.

Hyperextension discouraged without muscular support.

Iyengar Yoga

Muscular activation within poses emphasised (quadriceps lift kneecaps, inner thighs engage).

Passive “hanging” into joints is corrected.

Strength within length is a core teaching philosophy.

Shared Result

Reduced injury risk.

Functional mobility rather than laxity.

Neuromuscular integration.

5. Scapular Organisation & Upper Body Alignment

Common Principle: Shoulder girdle stability with expressive arm movement.

Ballet

Scapulae glide downward and outward while arms remain buoyant.

Avoid shoulder elevation or winging.

Neck remains long and free for aesthetic line.

Iyengar Yoga

Strong cues for scapular placement (e.g., broaden collarbones, draw shoulder blades into back).

Serratus anterior and lower trapezius engagement encouraged.

Arm positions built on stable scapular base.

Shared Benefit

Prevention of impingement.

Efficient force transmission through arms.

Freedom of movement without tension.

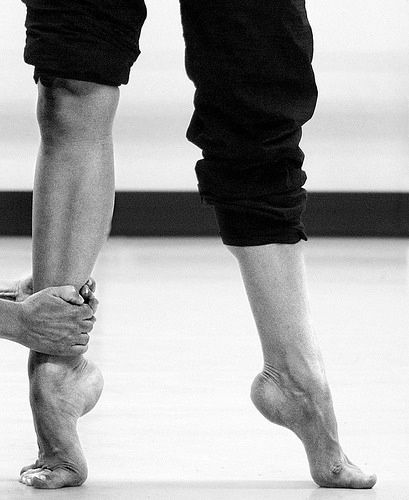

6. Foot Architecture & Ground Reaction Force

Common Principle: The feet are foundational for whole-body alignment.

Ballet

Tripod foot: heel, big toe mound, little toe mound.

Active arches and toe articulation in demi-pointe and relevé.

Grounding through metatarsals while lifting through medial arch.

Iyengar Yoga

Strong attention to spreading toes and evenly distributing weight.

Inner ankle lift and outer heel grounding.

Standing poses build foot intelligence and ankle stability.

Shared Concept

Upward kinetic chain begins at the foot.

Proper grounding enhances balance and alignment above.

7. Core Integration & Pelvic Neutrality

Common Principle: Deep core supports posture rather than superficial bracing.

Ballet

Transversus abdominis and pelvic floor engagement for stability in turns and balances.

Pelvis held neutral to allow freedom of leg movement.

Avoid gripping glutes excessively.

Iyengar Yoga

Pelvic positioning refined through precise cues.

Engagement balanced with relaxation to maintain breath.

Core activation integrated with spinal length.

Shared Goal

Dynamic stability.

Efficient movement initiation from centre.

8. Breath & Neuromuscular Awareness

Common Principle: Conscious control enhances alignment.

Ballet

Breath supports phrasing and fluidity.

Awareness of tension patterns essential for clean lines.

Teachers cue subtle muscular refinement.

Iyengar Yoga

Breath used as alignment feedback (restricted breath often signals misalignment).

Slow holding of poses increases proprioception.

Mindful observation of asymmetry.

Shared Outcome

Higher body awareness.

Precision in motor control.

PART TWO

How These Alignment Principles Translate to Everyday Posture

While ballet technique and Iyengar yoga are often associated with dancers and dedicated practitioners, the underlying alignment principles are highly relevant to modern bodies shaped by long hours of sitting, screen use, and repetitive movement patterns.

Many of the postural issues people bring into class are not dramatic injuries — but subtle structural habits that gradually create discomfort, fatigue, and inefficient movement.

Here are some of the most common upper-body and spinal patterns I see — and how alignment-focused training begins to address them:

Forward Head & Neck Tension

Chin drifting forward from prolonged phone or laptop use

Overactive neck muscles and reduced deep cervical support

Difficulty maintaining upright posture without fatigue→ Ballet-inspired axial elongation and Iyengar-based stacking cues help restore head–spine alignment and reduce unnecessary muscular strain.

Rounded Shoulders & Collapsed Chest

Internally rotated shoulders from desk work and device use

Limited thoracic extension and shallow breathing patterns

Arm movement initiated from tension rather than stability→ Scapular organisation, port de bras mechanics, and precise arm positioning retrain shoulder placement while restoring openness across the collarbones.

Thoracic Kyphosis / Upper Back Slouching

Habitual flexed posture leading to stiffness and reduced spinal mobility

Difficulty maintaining vertical lift without gripping the lower back

Feeling “compressed” through the ribcage→ Directional energy cues and spinal length work build active extension through the upper back without forcing rigidity.

Rib Flare & Overarching the Lower Back

Compensatory posture when trying to “stand up straight”

Loss of true core integration and unstable spinal stacking

Excessive tension through lumbar spine→ Deep core integration and pelvic neutrality principles teach upright posture through support rather than overextension.

Shoulder Elevation & Neck Compression

Shoulders creeping upward during arm movement or stress

Limited scapular control and inefficient upper-body mechanics→ Coordinated scapular stability and breath awareness help restore freedom through the neck and ease through the shoulders.

Collapsed Upper Body During Sitting & Standing

Passive hanging into joints rather than active structural support

Reduced proprioception and body awareness→ Geometric alignment frameworks and proprioceptive training help students recognise and reorganise posture in daily life.

Rather than forcing a “perfect posture,” ballet-inspired alignment and Iyengar-informed teaching cultivate awareness, strength, and structural intelligence — allowing posture to emerge as a natural outcome of coordinated, efficient movement.

🩰 Alignment Tips for Real Life: Movement Matters More Than “Perfect Posture”

It’s important to understand: posture isn’t inherently good or bad. Slouching or rounding your back isn’t the issue — the problem is staying in the same position for hours without moving. When the body remains static, muscles tighten, joints lose mobility, and other areas become stiff.

The goal isn’t forcing yourself to sit “perfectly straight.” It’s about moving regularly and bringing awareness to your body, especially while standing and walking — the easiest times to reconnect with alignment.

Simple Alignment Checks & Habits

Head & Neck:

Imagine the crown of your head lifting gently while the back of your neck lengthens.

Look forward instead of down at screens to reduce neck strain.

Shoulders & Chest:

Let your shoulders drop away from your ears.

Lift your sternum and lengthen through the front of your body — from abdomen to chest — while keeping your shoulder blades gently sliding down and slightly apart.

Thoracic Spine (Upper Back):

Stand tall but relaxed, imagining a string lifting from the top of your head.

Roll your shoulders or gently extend your upper back against a wall if it feels stiff.

Pelvis & Core:

Find your neutral pelvis when standing, engaging your deep core (transversus abdominis and pelvic floor).

Avoid locking your lower back into an exaggerated arch.

Feet & Grounding:

Spread your weight evenly across both feet.

Test your balance: lift all ten toes slightly off the ground, then reconnect the big toe mound and the outer heel. This helps you feel whether your weight is shifting too far forward.

Press through the heel, big toe mound, and little toe mound — this naturally stacks your body from the ground up.

Practical Movement Reminders

Stand up and stretch every 20–30 minutes, or at least once an hour.

Walk a few steps, do gentle twists, or roll the shoulders — even brief movement keeps joints and muscles active.

While sitting, make small micro-adjustments: shift your weight, uncross your legs, or lengthen through your spine for a few breaths.

Bottom line: It’s not about perfect posture — it’s about keeping your body mobile and aware. By moving regularly and checking in with your alignment while standing or walking, you prevent stiffness, tension, and long-term restrictions.

Key Difference

Even though alignment philosophy is similar:

Ballet prioritises dynamic movement aesthetics and performance.

Iyengar yoga prioritises therapeutic alignment, structural balance, and sustained positioning.

Yet both share a highly analytical, almost architectural approach to the body.

While ballet and Iyengar yoga may look very different on the surface — one performed under stage lights, the other practised quietly on a mat — both reveal a shared blueprint for how the human body organises itself with strength, efficiency, and grace.

Their common language of oppositional energy, geometric alignment, and conscious muscular activation offers more than just aesthetic posture; it provides a pathway toward resilient movement and long-term structural health.

When we learn to stand, move, and stabilise like this, posture stops being something we “force” — and becomes something we embody naturally.

If this approach to alignment resonates with you — where movement is precise, intelligent, and supportive of long-term posture — you can explore these principles further through my structured, anatomy-informed sessions designed to build resilience, balance, and confident movement.

🔎 Explore Further

Strength & Mobility — develop structural strength, active stability, and intelligent movement patterns

Yoga & Mat Pilates — refine alignment, body awareness, and controlled mobility

Reformer Pilates — resistance-based training for posture, coordination, and muscular balance

Postural Imbalance Support — targeted work for asymmetry, recurring tension, and structural re-education

Comments