"No Pain, No Gain"? You're Missing the Point

- Sheela Cheong

- Apr 30, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Jun 21, 2025

Do you find yourself pushing through pain during your workouts?

Many people do — often because they’ve been taught that discomfort is just part of the process. But here’s the truth: your workout should not be painful.

Yes, it can be challenging. Yes, your muscles may burn or fatigue. But sharp pain, strain, or persistent discomfort is your body’s way of saying something isn’t working well — and ignoring that isn’t strength. It’s a missed opportunity to train smarter.

“Listen to your body” isn’t some feel-good, woo-woo advice.

It’s about building a real, functional mind-body connection — what we call neuromuscular awareness.

That’s your brain's ability to sense, understand, and control how your muscles are working in real time.

And when that connection is strong, your movement becomes more efficient, powerful, and safe.

The story below is about someone who’s been learning to do just that: tuning into how her body actually feels during exercise, and making small changes that lead to more strength, less pain, and long-term results.

These messages are from a friend I’ve been working with who’s been consistently going to the gym. She’s strong, motivated, and committed—but she also has a structural issue in her hips that she’s had since she was young, and it really affects how she moves.

Her femurs (thigh bones) turn inward, which makes it hard for her to get her legs into a parallel position, whether she’s walking or exercising. Her feet tend to point inward, and her gait has never felt particularly balanced or tidy.

What’s important to understand is that this isn’t a flexibility issue. It’s not about tight muscles—it’s about how her bones are shaped. Her hip alignment is limited by her structure, not her stretch.

So instead of trying to “fix” how her legs look in parallel, our focus is on strengthening the muscles that haven’t been doing their fair share of the work. Her glutes (that’s glute max, med, and min), hip flexors, and hamstrings are all on the weaker side, and we’re slowly working to strengthen them. This will help her body feel more supported from the inside out—so she can move with more ease, balance, and long-term comfort.

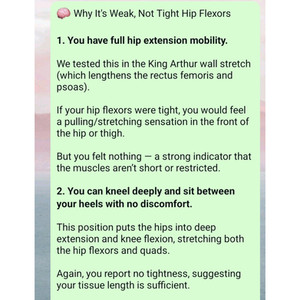

She’s often told by others that her hips are “tight,” but based on what I’ve seen, they’re actually under-supported.

When we tried deep hip flexion and internal rotation positions—like the King Arthur stretch at the wall, or Virasana (kneeling and sitting between the heels)—she got into both easily, without feeling any strong stretch in the front of her hips or thighs. That’s a good sign that her hip flexors aren’t actually short or restricted.

In the second text she sent me, she mentioned that she tried to explain this to her gym coach:

“I tried to tell S that it isn't so much tight hip flexors, but weak hip flexors, but I feel like I don't know enough about anatomy to explain it to her.”

So I wrote these messages (above) out to help her better understand what’s going on in her body—and to give her the language to explain it with confidence when she’s talking to her trainer.

One of the biggest shifts in our work together has been helping her tune in to how her body feels during movement. She’s gotten so used to feeling discomfort—or even pain—during workouts, that pushing through it has just become her default.

In our sessions, I regularly ask her what she’s feeling, and whether anything hurts or feels like strain. At first, she didn’t always know how to answer, which is completely understandable. But she’s been really open to learning, and has started to understand why I keep checking in: because movement isn’t supposed to hurt.

She often feels discomfort in her hip flexors and inner thigh (groin area)—muscles that are chronically overworked because they’ve been compensating for weak glutes. This became immediately clear in our last session.

When she tried a side-lying exercise with ankle weights, it hurt immediately. Instead of having her push through it, I paused the exercise, removed the weights and asked her to fully relax her leg into my hands. This gave her overactive hip and inner thigh muscles a chance to switch off. I wanted her to experience that sense of release before even attempting the movement again.

Then we restarted the movement very slowly and gently. I had her place her hand on the side of her hip to feel for her glute medius switching on—that’s the muscle I wanted her to lead with. That simple awareness shift made all the difference.

Ultimately, our goal isn’t to change her bone structure or force a perfect alignment—but to improve muscle balance, increase body awareness, and build the strength she needs to feel stable and supported in her movements, whether she’s walking or doing strength work at the gym.

"No pain, no gain?" This is my answer:

Comments